Selling Art

I’ve been selling art for a while now. I’m counting the years in my head—18 perhaps—not quite two decades. When I’m searching for documents on backup drives, I run across whole folders of paintings I’ve completely forgotten about. I see them and recall the details of my path more precisely than I ever would have, had my memory not been jogged by those images of paintings that left my life long ago, because other people wanted them.

Early in those 18 years, a watercolor instructor of mine had our class cover a piece of paper lightly, letting the pigments mingle by themselves. After the application dried, we traced leaves on this multi-colored background. We darkened the negative space around the leaves matching the colors on the paper as they had run into one another. She told us to trace the shapes again and darken the negative space that was left after that. We repeated the process with a third layer. She allowed us to stop at three, but I kept going until the tiny bits of negative space left after I traced my final layer of leaves was nearly black. I was hooked on the process and, already being addicted to botany, I cut out the shapes of eastern oaks, sassafras, and tulip trees. I layered them. I layered trilliums, ladies’ slippers, blackberry briars, California poppies, Indian Paint Brush, Bloodroot. I continued with butterflies and beetles. These are only the ones I recall. I suspect there were more. One of them looked like wall paper from the sixties, so that’s what I named it. From this exercise, I learned how to darken almost every color I could create from my palette until it reached its darkest, nearly black value. I became better at holding my brush and applying washes, and at creating nice neat edges only where I wanted them. That instructor knew what she was doing when she made this assignment.

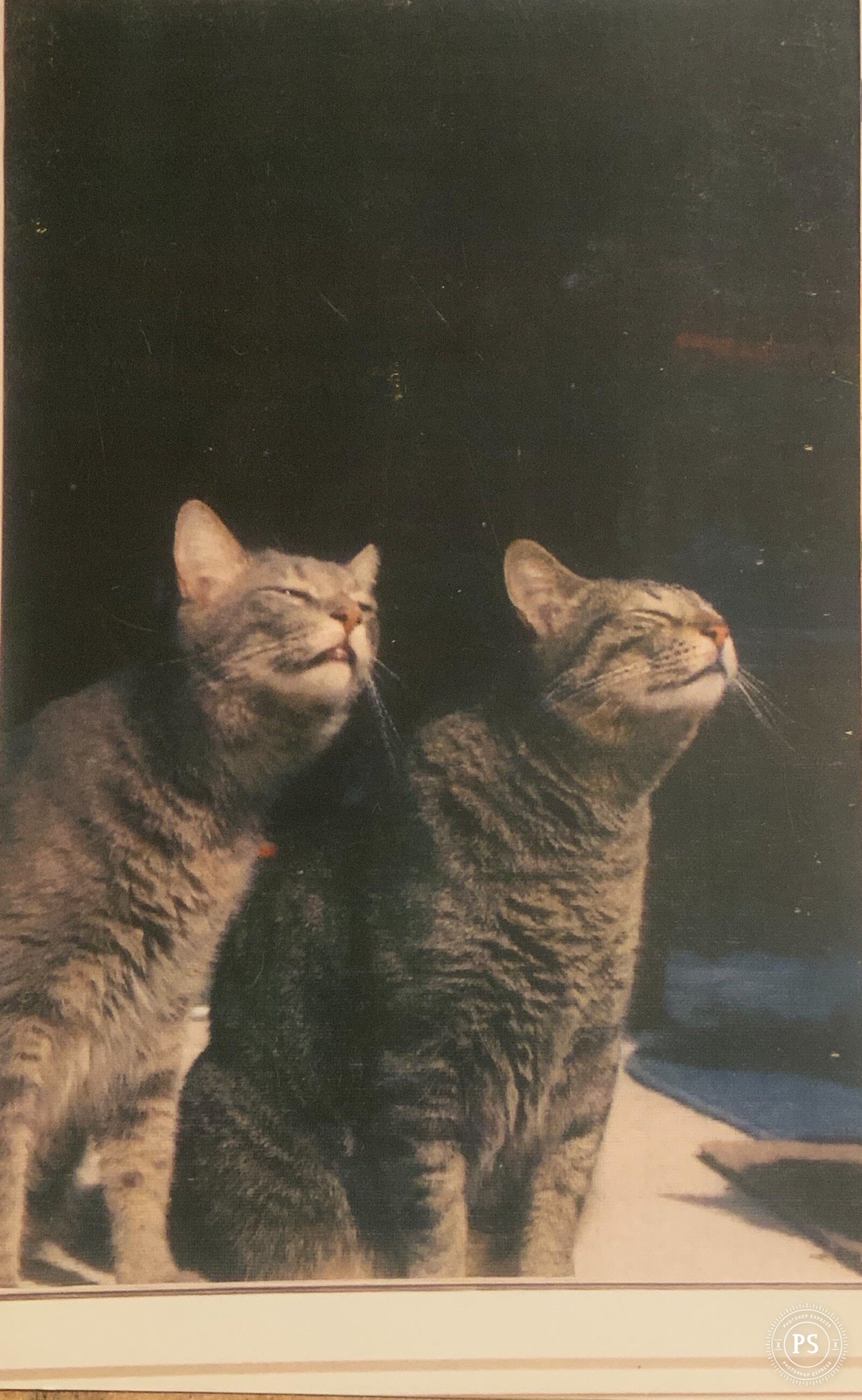

I was good at matting and framing my layered silhouettes— and my other paintings—at very little cost. I found mats on sale at Michaels. I went to Goodwill for frames. I learned to cut mats myself. I also photographed my paintings and made greeting cards, as many artists do. I became as obsessed with greeting cards as I had with layering shapes and I added more cards to my selection from my photography. I had a series that featured our cats as they sniffed the air at our back door, slept belly up, sat on my computer while I tried to work, and chomped down on the toilet bowl brush we used to comb their fur. I had a series of wildflowers, of sunsets, of natural abstracts. I was full of energy and hope. For a brief moment I thought about what customers might want to purchase, what could I paint or photograph that the public would like. I quickly abandoned that train of thought. I had to paint what I wanted to paint and photograph what called me. Consequently, I ended up with cards that featured everything from lupine and California poppies to the patterns of light reflected in our bathroom doorknob and of the ice crystals on the windshield of our ancient Volvo station wagon. I was in the middle of my visual heyday and I saw, really absorbed what I was looking at, all around me.

On Saturday mornings I packed all this stuff into that Volvo station wagon and drove to the parking lot on the corner across from Peet’s Coffee on the Alameda in San Jose. There, a small, independent farmer’s market assembled from 7AM to early afternoon. Whoever was organizing it allowed me to sell my art, when the association that ran the other farmers’ markets in Santa Clara County would not. I had a canopy, but no panels. I don’t recall how I displayed my framed work, but I remember the wind blowing one wall down and, very luckily, I lost the glass covering for only one painting. I do recall the brightly colored, oversized shoestrings I purchased at a dollar store. I strung the shoestrings from the canopy entrance and used clothespins to attach my greeting cards to them. I didn’t have nicely fitted cellophane sleeves for the cards—I didn’t know where to get them—I didn’t even think about it. My cards were housed in ziplock bags. They fluttered in the breeze on the giant shoestrings, inviting people into my booth. Occasionally, the breeze would liberate a few of the cards, so I searched for a better way to attach them to the shoestrings. I settled upon a slew of tiny, multi-colored, binder clips that sparkled in the sunlight. To prepare for set up at the farmers’ market, I tied the clips into the shoestrings about a card’s space from one another. At the farmers’ market, I snapped the cards into place. They continued to flutter invitingly, but they no longer flew away.

Quickly I learned that I could get the canopy and paintings up by 7 and then take my time hanging the greeting cards. From 7 to 11 shoppers were dedicated to the mission of purchasing produce. My art rarely sold during that time slot. The wanderers, people who were out to shop for fun, began to filter in after 11 am. They purchased my cards and, on good days, a matted painting. On very good days, a framed painting would sell.

After they fulfilled their major missions, even some of the produce shoppers dropped in. They were the ones who returned the ziplock bags the weekend after they purchased my cards. They thought I might reuse the bags. I thanked them and I did.

There are specific sales I recall. One woman was immediately drawn to a door I had painted as an assignment by the silhouette instructor. The woman looked at me and asked, “Is it really only this much?” I nodded and sold it to her. In another painting, jacaranda trees lined a road near my home. The trees were in full bloom and I had not been able to bring myself to put any cars on the road—not even parked ones—although the road was clearly in a neighborhood full of houses. Consequently, I had named the painting “Nirvana: San Jose without Cars.” I hoped those of Indian descent who passed through my booth would not be offended by my co-opting a concept from their religious heritage. A sari-clad woman, with a clearly identifiable Indian accent, walked straight toward that painting, put her hands on the frame and said, “This is beautiful!” The color of jacaranda blossoms was dominant in her sari. She purchased the painting, never making a comment about the title. One of my favorites of the layered paintings, the silhouetted butterflies, did not sell for weeks. I couldn’t understand it, but one morning—at about 11 o’clock—another Indian woman, whose sari coordinated with the butterflies, purchased it. A couple who collected art that reminded them of California wandered through my booth several times. They liked my stuff, but it didn’t fit their theme. Apparently, they weren’t into botany as deeply as I was, or they would have recognized all the California native plants scattered everywhere in my tent. One morning I hung a pastel I’d done en plein air. It was a California oak on a hillside. The painting was there until around noon, when the couple arrived. Apparently, as plants, oaks were large enough to register as distinctly Californian in their eyes.

Finally, among the purchases I specifically remember, there were three full sheet watercolor paintings I had matted myself (Michaels does not carry mats for 22 x 30 inch images). One was the silhouetted poppies that burst forth from a base of their silhouetted leaves, the second was a puzzle of fractured pansies and the third was a colorful rendition of arroyo lupine. I didn’t expect these to sell because of their size, though I secretly thought the poppies would, because they were so fun to look at. (Now who was I keeping that a secret from, myself?) Every year, a neighborhood Rose Parade traveled the Alameda. During the time I spent at the farmer’s market, the organizers of the parade invited merchants and artists and crafters to set up booths along the route. I don’t even think we had to pay a fee. The parade itself was for families. The floats were pulled by bicycles or were bicycles, and boxcars. My friend Susan was visiting from Texas and she sat the day under my canopy with me. A woman who worked in an office building across the street strolled in and chatted with us. She was tall and wore boots and a shawl. She had flare and a large, happy, generous personality. She spoke about decorating her new home. It was empty and she wanted to fill it with bright colors. She flipped quickly through my sling of matted work. When she reached the back, where the large paintings were, her eyes grew big. A few minutes later she was headed across the street with all three of those 22 x 30 paintings under her arm—the poppies, the lupine and the fractured pansies. My friend Susan said, “ I think she will never be able to have enough color in her life.” A few weeks later the woman stopped in my booth to say she had hung the poppy painting over her mantel. It was visible from the street and her neighbors and friends were always asking her what it was. She was thrilled, and if she had not verbalized it, her demeanor would have told me so.

There are also people who perused my cards that stick in my memory. One woman squealed when she reached the card depicting our older gray cat asleep on the window seat at our home. I had taken the photo so that you could see the large sunflower just outside the window. The bright flower seemed to be shining in on the sleeping cat. The woman said, “I need a retirement card for a friend. Isn’t this just a perfect card for retirement?” Apparently that card was perfect for a lot of occasions. It became my best seller and, to this day, I have sold more of nothing else I have ever sold, not even one of my books. Another of the card perusers I recall was an older young man—you know—probably late 20s or early 30s. He looked like he might be headed for Woodstock. He was particularly drawn to some of my more abstract cards and pointed out the ones most customers passed over: the natural abstracts that were only swathes of color, the rock faces, ice on the Volvo windshield and the pattern of light on the doorknob. He didn’t purchase anything, but I enjoyed talking with him. Later, before the market closed, he dashed into my booth. He had returned from somewhere down the street to purchase the doorknob card. I also recall a father and his 6 or 7 year-old son who looked at every photo of an animal I had: the coyote, the moose, the buffalo, all the birds, every one of the cat photos. The father touched one of the cat cards that was hanging close to the top of the canopy. “Look,” he said to his son. “Can you see?” When his son, standing on tip toe, nodded, the father continued, “Can you see their noses? They’re smelling the air.” The boy nodded again. The father turned to me. “This is my favorite,” he declared. Little did he know how much I wanted to paint that scene, how much I loved those cats, or how fortunate I had been to be in our back yard—with a camera—when I caught sight of them at the screen of our big sliding glass door, with their noses in the air. It would be nearly the entire stretch of the 18 years of my selling art before I would capture that scene in pastel.

To my delight, every weekend, just before closing time. the produce sellers slashed their prices in half. I visited every booth, purchasing something. Many times the sellers refused my money or took only half of half the price. I came home with vegetables for the week and more fruit than was possible to eat before it spoiled, so I cooked the fruit into a slurry of natural sweetness. I put some in the fridge to eat right away and froze the rest. My husband teased that I used all my art profits to purchase the fruit and vegetables, but I shook my head, telling him about the generosity of the other sellers and how I felt I was part of some kind of fraternity that took care of its own. All week I defrosted the fruit slurry and used it to top everything from pancakes to ice cream. I savored the fruit and the generosity of the other sellers.

I miss the energy and relentless hope I felt as I packed my canopy and paintings into my car during that period of my selling career. I miss the exploding color in those silhouetted poppies. My art is different now—maybe more sophisticated, but not necessarily better. What I learned—the lesson that unfolded before me while I occupied my booth at that small farmer’s market— was that eventually the person that fits a painting appears. Selling art isn’t about creating scenes that people will like—it’s not about making art that will be pleasing to the public. It’s about waiting for the person that fits the art to discover it. Someone will come along whose cat sleeps in that exact position. A woman will declare that she held her sister’s hand and trudged back from the beach for lunch nearly every weekend of their childhood—“just like the two girls in your painting.” A husband will sneak in to purchase a blustery scene of a child gathering fruit: “My wife loved this and her birthday is next week.” He may be enjoying the procurement of the painting as much as she will enjoy having it. Someone will say simply, “This makes me so happy when I look at it.” These are the ways my work exits my life.

Sometimes I get a glimpse of my paintings in their lives beyond my booth. People send me photos of the art hanging on their walls, but this is rare. Mostly these come from family members and close friends. Occasionally, I have been shown my abstracts in homes when i did not recognize the works at all. Their new owners have reframed them and hung them upside down or sideways, changing the way I cropped the images in their mats. However, the people who purchased the paintings and reframed them in these unrecognizable ways are completely satisfied with their acquisitions. I do not argue. What was a painting in my booth has now become a painting in a relationship with its owner. I suspect sometime in the future I may encounter a piece or two of my work at a yard sale or in a thrift store. Eighteen years is a long time and all the relationships I have launched are not likely to have lasted in this highly mobile society.

I don’t go out with my canopy as often as I used to, but when I do, I usually sell something. Someone who fits one of my paintings usually appears, and that keeps me hooked on selling my visual art. I am experimenting with online sales, but I don’t think online selling will be as satisfying as sitting beneath my canopy, for I will not witness the match that is made between an image and its recipient. No marketing method has a chance of making a dent in my inventory anyway. The inventory constantly restocks itself because I seem not to be able to stop painting, even though I prefer to write. Words are my first and my most natural medium. Unfortunately, writing takes more time than painting, collage or photography, but on the plus side, it does not involve mats or frames. And words take up much less space when they don’t sell.

These days, my paintings have joined my words inside my picture books, and my picture books have joined my paintings under my canopy. I have a website and I have made sales online. My younger colleagues assure me that I may build relationships with the people who purchase my paintings via the internet. What I have found so far is that online purchases of my art and books mostly involve people I already know very well. When I think back about my days at the farmers’ market, all the energy I possessed and the relentless hope that possessed me, I know I will never quite feel like that again. However, I did manage to get around to painting the cats with their noses in the air, searching for smells in the morning sunlight. When I finish one book, another begins to form in my head. I suppose the energy that allowed me to pack the Volvo every Saturday has merely changed forms and fuels other kinds of activities, as if some kind of law of conservation applies to my creative endeavors the way that laws of conservation apply to momentum and mass in physics. I’m counting on that, because I wish always to have sufficient energy and hope to move on to the next iteration of selling my art.